Stories Talk | Presentation Skills and Effective Storytelling

Stories Talk | Presentation Skills and Effective Storytelling

By Mia Kollia

Translated by Alexandros Theodoropoulos

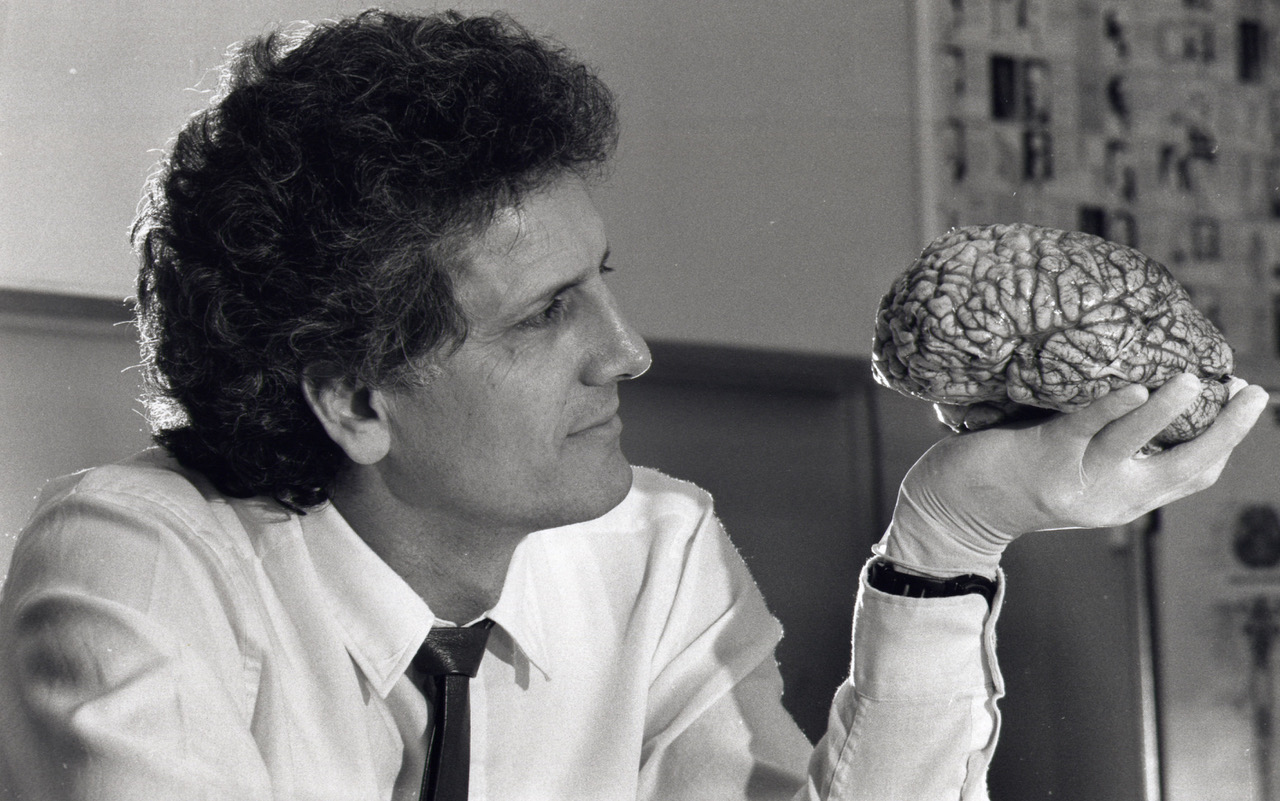

He is approachable, but not always easy to understand, he loves the environment - he could be a political leader in such a global movement and he would definitely like to save the pedestrians of Athens! He grew up in Ithaca, being poor but happy and feels he owes his solid foundation at school. A diverse and great personality that our mind cannot conceive opens his heart - perhaps the time he missed his children makes him sad. But he replaces that time with his grandchildren.

- Scientifically speaking, at what level do you think our country is?

We used to be at a good level. Now, especially after the 2011 crisis, I don’t know where our ranking stands. Regarding my field, I know a lot of people who work very well, doing research under the adverse research conditions that exist in Greece. However, it is a pity, because this is how a key asset of the country is lost - when so many young, educated people, leave for other countries. In other words, it is a pity for Greece to have free education, to invest in a child from kindergarten to elementary school, junior high school, high school and then to higher education, but eventually that child ends up going to another country to work. And finally, our country has more well-educated emigrants per capita than any other country.

- Why did you choose to live in Australia and not in the US?

I got my degree in California, from USC Berkeley University. In Canada, I did my PhD at McGill, then I returned to the US for an annual post-doc at Yale, and then I got a job opportunity in Australia.

- How is Australia and its people?

Australians are very calm people. I really like Australia. The state operates well at all levels and doesn’t have the problems we see for example in the USA. Especially in matters of racial equality, the situation in the US was very bad. Coming to Australia I saw a big difference and felt much better. Australians are well aware that in the past they were convicts who went there for punishment. They were very much inspired by the values of the Enlightenment and tried to create a state based on equality.

Of course, there is a persistent mismanagement of Australia's indigenous people, with worse living conditions, fewer opportunities and lower life expectancy because of all that I have mentioned. The gap in this area of social justice has not yet closed.

- When did you realise that you were strong in your subject and wanted to be engaged with it?

At first I did not think I was very good. My only goal was to get to a university. I was lucky to have an inspirational professor in psychology and he got me interested in my field. Then, when I was in Cambridge, I saw that parts of the brain had already been mapped, such as those related to eating and drinking, as well as aggression and sexual behavior, and how the brain regulates these functions, and that fascinated me.

- A dedicated and renowned scientist definitely dedicates most of his life to his science. Do you find time for the rest of the things in your life?

I'm lucky because brains are the same! Basically, the brain of a rat and a human is about 80% similar, while that of monkeys is almost 100% similar. So it becomes relatively easy for someone who wants to have surgery on an area of a person's brain to find the area they want. After so many years of dealing with this issue, you start to feel more comfortable when you work in your field. In recent years, I have devoted most of my time to writing a novel, "In the Image" (Libani Publications, 2015). I put a lot of energy into it - it's much harder to write literature than a research paper. I took writing classes, I went to class… back to school because it was something I was interested in and I didn’t know it well. So, yes, I realise I've got some science and study, but this is my life – I don’t consider it out of the rest of my life.

-The environment is very important for you – maybe as important as the brain…

In 1969, I read some articles in scientific journals about the ozone hole, which has been of great concern to scientists ever since. I have continued to pursue the issue to this day through my position at the Australian Academy of Sciences. Australia is now at risk of losing its coral reefs (areas as large as Italy) - in a country where about 1/3 of marine life depends on corals. In the last two years, about 40% of their forests have been lost to fires and 4 billion animals have lost their lives. We are talking about a huge loss. Many scientists, through our academies, try to push governments to protect the environment, locally and nationally.

Unfortunately, the lobbies of the mining companies have a lot of money at their disposal and they are gaining a lot of power in politics and therefore in relevant decision-making. However, everything you do in life is relevant.

To me, research is like opening a puzzle. When I find an area of the human brain that corresponds to the same area of a monkey or a rat that is satisfaction! I don’t necessarily do it to help medical science - I do it because I like it, it satisfies me. It is wonderful to see how, 400 million years ago, brains like those of birds were created, and how nature affected their development leading to the development of the human brain. But if someone asks me "What did you actually do?" I think my action to protect the environment is what I am really proud of.

- I imagine that your contribution to medicine is great. Doesn't that give you extra satisfaction?

Of course it satisfies me. Scientists are very interested in their reputation among other scientists and not particularly in how the public sees them. So you usually look for work references that have been made and are being made by other scientists. My first book, which dealt with rat brain mapping, managed to become the number three book in most references in other scientific papers.

This is because neuroscientists, physiologists, anatomists, psychologists and psychiatrists need this book, just as a traveler needs his map. Based on such maps, these scientists can construct models of brain diseases, such as schizophrenia, Alzheimer's or epilepsy, in rat brains. Next, they need to find the match between the brains of rats and humans so that they can create a drug. We provide these maps for the researcher to use, which is why all these references are made. Atlas is a tool that contains the coordinates for travel within the brain.

- What are we? Where did we come from? Have you answered that?

Scientists and archaeologists know how to answer exactly where we came from. Greeks and Cypriots had a genetic link 2,000 years ago. Greeks and Norwegians had a genetic link 10,000 years ago. We and the chimpanzees separated about 5-7 million years ago. We have a common ancestor, we are cousins. 7 million years ago there were no people. We have similarities even with birds, from ancient times - we have been separated for 400 million years.

- Soul - mind - brain. How do we define these concepts?

The brain is the natural organ. The mind is the energy of the brain, that is how it works and when the brain stops working, the mind disappears. The term soul is useless. The vast majority of neuroscientists do not consider the term "soul" necessary. People should abandon the illusion that there is a soul, since everything comes from and is controlled by the brain.

- So, expression of emotions is not the soul of every human being?

If you want to give it that meaning, there is no problem, but science does not accept it, because there is no reason. There is already an organ that performs these functions and it is none other than the brain.

- For example when a person goes to the psychologist and tells him that while logic dictates him to not be with someone but feelings don’t allow him to get rid of that someone, what happens in this case? Shouldn't logic be enough, according to what you say?

The brain informs you that you love Paul, let's say. You want to get rid of Paul, because you see that he is not worth your love. "You didn’t deserve love, you didn’t deserve affection", says the song, and yet you see that you have no ability to direct your love. There are two factors. First, the genetic predisposition, that is, you are predisposed to love a man and not a bird, because it is another species. Second, the environment.

Who knows exactly what created your taste. If there is one strong indication that there is no freedom in love, it is this. Many times we see a man who while being rejected by a woman, he still bothers her - he can even use force against her or commit suicide. And all this happens because we don’t understand neuroscience; just as he cannot deny his love for her, so she can no longer love him. In the emotional field, e.g. in love, there is no free will. You cannot direct your emotions with your will.

- Then how can we live in a society without violence and without abuse? Are you telling me that it is something we can’t avoid?

Neuroscience says that we are the offspring of experiences in which we have no choice. We didn’t choose who would give birth to us or if our mother smoked during pregnancy. From there, the environment begins to affect us. Negative environments have negative effects. We are the slaves of yesterday. Behind every move, decision, thought, there is a structured environment that puts you in the position of the victim or the perpetrator.

- Would you see in the future neuroscientists trying to intervene in the human brain to improve some functions?

Even today there are some surgeries, such as those related to epilepsy, but in general I don’t see that happen.

- Is there any way to delay dementia or Alzheimer's if we are prone to get it at some point in our lives?

Exercise is the only thing that can delay dementia and Alzheimer's - neither sudoku nor crossword puzzles can do so. That is why we must free the sidewalks of Athens from cars, so that people can walk. Also, poor people have more factors that push them to the manifestation of dementia, regardless of educational level.

- Do scientists admit their mistakes? Can you stand that?

One thing that is different between science and religion is that in science we have doubt in the face of evidence while in religion we have faith without evidence. Nothing pleases a scientist more than to come up with another scientist's theory. In science there is competition, not religion. A scientist will admit his mistake, because in any way possible, another scientist will sooner or later converge or deviate from the theory or discovery of the former.

- You have lived being poor as a child…

The first years were difficult. We were all poor in Ithaca; Poor, but not unhappy. I was a child of a large family in post-war and civil-war Greece. I didn’t know my father well, he was in the Resistance and then he left for America with my brother illegally, being chased. Strange years.

- When did you encounter your biggest difficulties?

That was when I went to the United States and had to work weekends, a time I would like to dedicate to my classes. In fact, when we were on vacation from college, I got two jobs - one during the day and another at night. I had to show great perseverance and dedication not to drop out of my studies. This first step was the most difficult.

- What do you think about your… brain? It’s the result of what factors?

If you ask me whether I was better than others, I would say that others were not better than me. I knew that if I read more, I would take one more step - and the next step brought one more and another one more… My teachers from Ithaca also did a very good job. Private tutoring did not exist back then. But when I went to Berkeley, I realised that I wasn’t lagged behind in knowledge acquisition. In general, however, if you love what you do, you will perform well. At least that's what I did; I followed… my nose, as the British say.

#HisStory