Stories Talk | Presentation Skills and Effective Storytelling

Stories Talk | Presentation Skills and Effective Storytelling

By Mia Kollia

Translated by Alexandros Theodoropoulos

"Education is not the few or many letters; it is the preparation of each person for life, according to their abilities, a principle which the senior and junior inside the ministry, as well as the employees outside, have proved that they ignore. Some of them have been there for 15 years. Three others served three terms as Ministers, but only one thing concerned them all: the party, that is, the demand for the satisfaction of their material ego. Because they are products of, as I said, derailed parody and not products of real education.

The factory, whose purpose is to produce this moral oxygen - I mean the Ministry of Education - as evidenced by the state and social results: discomfort, poverty, contemptible partisanship, completely devoid of ideas, immigration, lack of a worthy clergy, lack of competent educators and national humiliation - I sadly say that it is saturated carbonate".

The above excerpt is from the book "What education really", a book of the last century. Its author is a woman who has left her golden mark on Greek education, dedicating her life to the education and progress of Greek women.

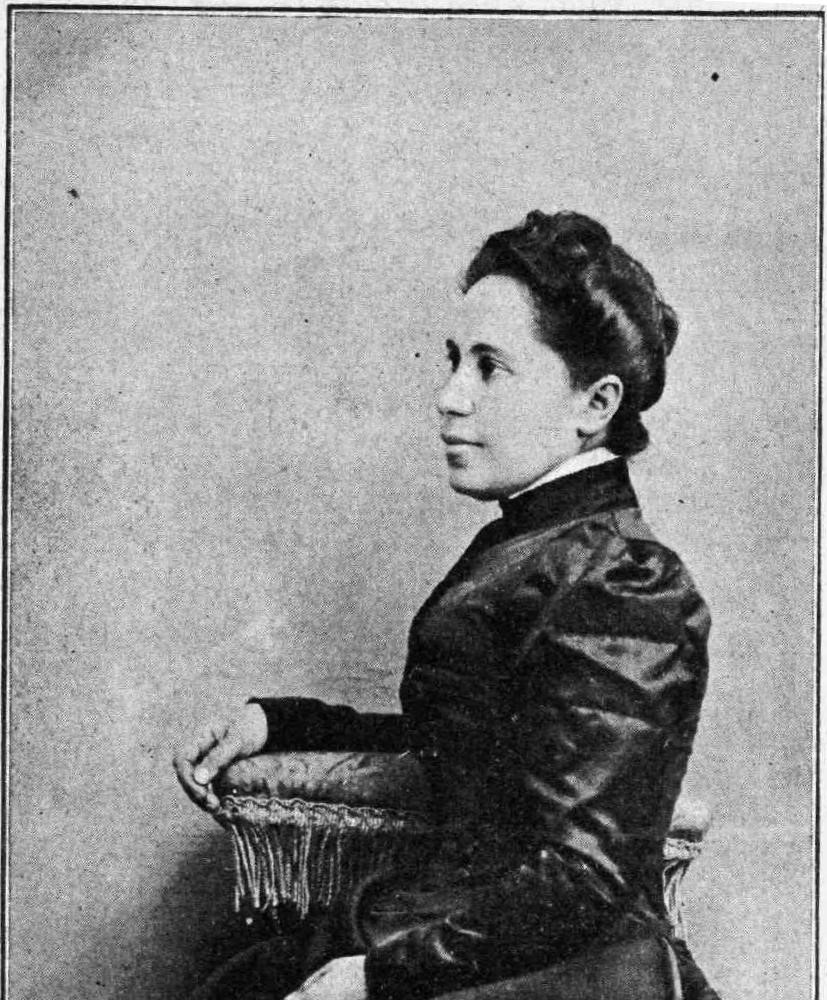

Sevasti Kallisperi, the first Greek student at Sorbonne.

We read in the "Journal of ladies" of the time (no. 48, 7/2/1888):

"Miss Kallisperi is made of iron will and unprecedented persistence. Nobody encouraged her, nobody supported her. […] Governments in Greece are cruel mothers to women. Keeping her away from letters when she was young, considering education as an exclusive privilege of men. Miss Kallisperi is appreciated and loved by everybody in France for her tireless alacrity […], with national pride we support and follow this line, wishing other fellow female citizens to follow this great example of hers…”

She was the daughter of a good and progressive family and as soon as she graduated from the private Hill Girls’ School, she set out for the High School that would pave the way for her to go to University.

But in those years, as Kallirhoe Parren's feminist "Journal of Ladies" says, education was an exclusive prerogative of men. Only the "revolutionary" thought of Miss Kallisperi - that is, to dare to think of entering High School and then being admitted, like a man, to the University - caused awe and horror in the conservative society of the time.

As a result, she was educated in private lessons at home, like all proper daughters of well-to-do families deserve, and armed with a wealth of knowledge, she stood before a committee of teachers and excelled.

But as it was natural, this success was forcibly accepted and only after a lot of suffering she was awarded the high school diploma, of course without this meaning that the University door was opened to her. No way! That was indeed beyond the pale!

Thanks to her father's financial ability and open-mindedness, the ambitious and studious Sevasti sought knowledge and spiritual progress in Paris, leaving behind the patriarchal regime of her country. She passed the exams at the Sorbonne and entered the School of Philosophy. It was just 1885. In the next decade she became the first Greek female doctor of literature!

Returning to Greece she taught French and later Greek in Arsakeio school. However, she also taught private lessons at her home (1892). After resigning from Arsakeio, she became the first inspector of all girls' primary schools (1895), a position created especially for her.

As an intellectual and advocate of women's education, she strongly criticised the Greek education system and proposed ideas and bills to upgrade the public education of women of her time.

She was the first to suggest the school uniform for pupils: "from the domestic fabric of women's handicrafts and in a certain way that is simply a reminiscence of Greek attire" (Kallisperi, 1911: 216).

In 1897, the “Family” magazine published a proposal of hers entitled: "On the reform of women's education system". Her idea was to establish two-year schools of higher elementary education that would have a "literature department" as well as a "department of industrial education or women's real works". With this system, women would receive knowledge both to be able to pursue a profession and to be able to perform their household duties.

Two years later she submitted two educational bills to the Parliament; "On the establishment of Supreme State Girls’ Schools", "On Greek-friendly and more practical public education and on the establishment of a State Girls' School".

In 1904 she participated in the First Greek Education Conference, organised in Athens by the Association for the Distribution of Useful Books, which was in fact considered of reformist character!

She wrote books, translated foreign plays and dealt with ancient Greek literature.

Sevasti Kallisperi passed away in 1953 and left all her real estate in the Greek state.

#HerStory